From the very beginning of the First World War, some Slovenian and Croatian politicians bet on an Entente victory. Forced to flee Austria-Hungary in war conditions, they created two political centers of Yugoslav emigration in Rome (Italy) and Nis (Serbia). In January 1915, the Yugoslav Committee was established on the basis of the Rome center, which included major political figures from Croatia, Dalmatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Slovenia.

Having moved to London, the Yugoslav Committee began active political activities. It negotiated on behalf of the Yugoslav nations of Austria-Hungary with the governments of the Entente countries and Serbia, established connections with the Yugoslav diaspora in the United States and South America, promoted the recruitment of volunteers for the Serbian army and the collection of funds for Serbia and Montenegro. Branches of the Yugoslavian Committee were opened in Petrograd, Paris, Geneva and Washington.

The activities of the Yugoslav Committee provoked the most lively response from the Yugoslav peoples of Austria-Hungary. All the major political parties of Croatia and Slovenia were in solidarity with its activities.

In spite of the differences of opinion about the postwar future of the Yugoslavian lands, the leaders of the committee together managed to develop a program for the creation of a state of the South Slavs on the principles of a federation. The idea of a federal Yugoslavia was put forward in opposition to the idea of a “Greater Serbia,” which was held by the ruling nationalist circles in Belgrade.

Naturally, Yugoslavia could be created only with the dissolution of Austria-Hungary. But this prospect did not suit the financial circles of Paris and London, closely connected with the banking houses of Vienna. The British and French governments under their influence also did not allow the possibility of a “patchwork monarchy” to disintegrate. Another argument against the creation of Yugoslavia was the fear of England and France that it would strengthen Russia’s position in the Balkans. The strongest opponent of the creation of Yugoslavia, however, was Italy, who rightly feared the emergence of a strong competitor in the Adriatic.

During the war, with the participation of the Yugoslavian Committee in Russia, the formation of volunteer units from among the captured Yugoslavs, former members of the Austro-Hungarian army, began. Initially, Croatian and Slovenian prisoners of war, who expressed their desire to fight against the Austro-Hungarian Empire, were sent from Russia to the Serbian or Montenegrin armies. In the spring of 1916, after the defeat of Serbia and Montenegro, the 1st volunteer Serbian division was formed in Odessa from among the prisoners of war and after some time, the 2nd volunteer division formed with the 1st Serbian volunteer corps. Units of this corps together with the Russian troops fought in Dobrudja.

In the milieu of the Yugoslavian Corps for the first time appeared the contradictions which subsequently led to the disintegration of a united Yugoslavia. The fact is that the soldiers, former Croat and Slovenian prisoners of war, were mostly supporters of the Yugoslavian Federation. The officer corps was sent from Corfu and consisted almost entirely of Great Serbian chauvinists. As a result, a conflict began, which became particularly acute after the February Revolution in Russia. In spring 1917 representatives of Croatian and Slovenian soldiers and some officers of the corps addressed a declaration condemning the Great Serbian chauvinism, stating that the Corps was fighting for “a Yugoslavia, based on the principles of democracy and equality of all three nationalities”. In response, the Serbian corps command began a crackdown. At that time, a significant number of volunteer soldiers and officers withdrew from the corps and joined the Russian army. Under the threat of complete demoralization and collapse the command made formal concessions: the Serbian Volunteer Corps was renamed the Volunteer Corps of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

Subsequently, some of the soldiers and officers of the corps joined the Red Guard and took an active part in the Civil War in Russia on the side of the Reds. The names of the Red Serbian and Croatian commanders are well known: Oleko Dundich, Danila Serdich, August Barabash and others. In 1918 about 20 Yugoslavian military units operated in the Red Army. However, another part of the former members of the corps fought on the side of the Whites. Units of “White” Serbs and Croats fought near Murmansk, Arkhangelsk, Tsaritsyn, Astrakhan and Kazan.

In November 1916 the elderly Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph died. Austria-Hungary by this time was in a difficult situation. The 1916 campaign on the Russian front had been lost, and the country’s material resources were exhausted. 1917, the fourth year of the war, brought new disasters. There was an acute shortage of food, starving not only the population of the country, but also the army at the front. The weakness of the empire was evident.

The new Emperor Charles I, in the face of an apparent disaster, began to look for ways to conclude a separate peace with the Entente. The odious Hungarian prime minister, Count Istvan Tisza, was dismissed. In his Throne Speech to Parliament (Reichsrat) on May 30, 1917, Emperor Karl announced the need for reforms. He was followed by the leaders of the national movements of Austria-Hungary. On behalf of the Yugoslav faction (Yugoslavian Club), Slovenian deputy Anton Korošec made a speech that became known as the May Declaration. He proclaimed the necessity of uniting all the Yugoslavian lands, which were part of Austria-Hungary, into one state organism. There was no mention in the declaration of secession from the empire and the creation of Yugoslavia, but its promulgation drew a wide response. The declaration was supported by the Catholic Church in Slovenia and Croatia, the Serbian Metropolitan of Sarajevo, and a number of Yugoslav parties and organizations.

With the promulgation of the May declaration the final period of the struggle between the two currents actually began. Both these currents advocated the unification of all the Yugoslavian lands of Austria-Hungary into a single state-administrative entity, but some politicians saw this entity as part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, others as part of the federal Yugoslavia. The peak of the struggle of these currents came in the years 1917-1918, when the Habsburg Empire was already approaching its demise.

Complex processes were also taking place in another part of the Yugoslav political world – in the Serbian government in exile. The February Revolution in Russia severely undermined Serbia’s position in the Entente camp. Serbia lost its traditional foreign policy support in the form of the tsarist government. And the subsequent October coup in Petrograd and the Bolshevik seizure of power left Serbia virtually one-on-one with the rest of Europe.

In this situation, the Serbian ruling circles entered into serious negotiations with the emigrant Yugoslav Committee. In mid-June 1917, Prime Minister Nikola Pašić met with the leaders of the Yugoslav Committee on the island of Corfu. The initial positions of the parties in the negotiations were fundamentally different: Pashic and other Serbian nationalists stood for “Greater Serbia”, while the Yugoslav Committee stood for a federal Yugoslavia. But the foreign policy situation dictated the need for compromise: No one in the world was going to care for the interests of the southern Slavs anymore, and they had only themselves to rely on.

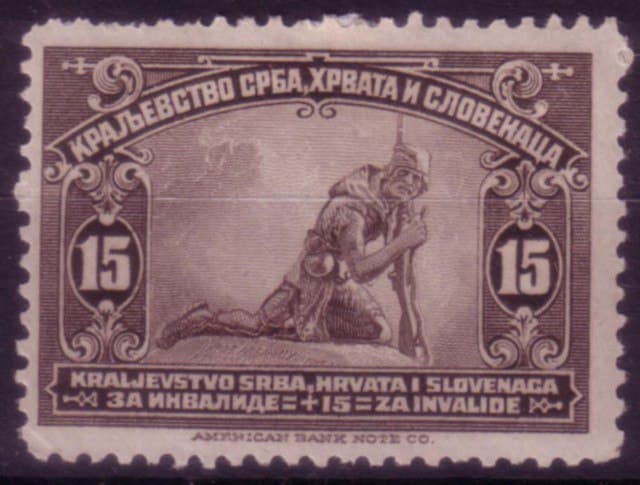

The long and difficult negotiations culminated in the signing of the Korfa Declaration of July 20, 1917, a political program for the creation of an independent South Slavic state. It was envisaged that the future state – the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes – would include all the Yugoslav lands of Austria-Hungary, Serbia and Montenegro. The constitution of the country would have to be elaborated by a specially called Constituent Assembly, but it was decided in advance that the new state would be a constitutional monarchy headed by the Karadjordjevic dynasty, rather than a federation.

The compromise nature of the Korf declaration was due to the unequal and precarious situation of both sides: the Serbian government that had been expelled from the occupied country had the army, and the Yugoslav committee had some financial resources and the support of the emigrants and part of the Yugoslav politicians of Austria-Hungary. However, both sides were literally suspended in the air – the war was still going on, and its outcome was not yet clear – and therefore needed each other. But the relationship was not balanced – yet the position of the Serbian side was stronger. After all, the Serbian government, although in exile, was recognized by the Entente states as a full ally and had real military power. Therefore, Great Serbian tendencies prevailed in the Corfu Declaration – and this was reflected subsequently in the entire history of interwar Yugoslavia.

In spite of all these shortcomings, the promulgation of the Korf Declaration aroused a wave of enthusiasm among all the Yugoslav peoples. Only the Montenegrin royal dynasty lost out – henceforth King Nicholas of Montenegro remained king without a kingdom. As early as March 1917, the Montenegrin emigrant Committee of National Unification was established in Paris, which on behalf of the people of Montenegro expressed solidarity with the principles of the Korf Declaration. The Montenegrin Committee established close contacts with the Yugoslavian Committee and the Serbian government. In response, King Nicholas and the Montenegrin emigrant government declared all Montenegrins who were supporters of the Korf Declaration “traitors.”

The beginning of 1918 was marked by the entry of the United States into the war. The advantage of the Entente became obvious to all. Without doubting his victory, on January 8, 1918, American President W. Wilson sent to the U.S. Congress his famous 14-point message, which outlined the concept of the postwar reorganization of Europe. Paragraph 10 read: “The peoples of Austria-Hungary… The peoples of Austria-Hungary must be given the freest and most favorable opportunity for autonomous development. Thus the first step toward the autonomy of the Yugoslav peoples of Austria-Hungary was taken at the international level. At the same time, there was still no talk of the collapse of the empire. “At this time we did not have in mind the complete dissolution of the Austrian monarchy,” wrote English Prime Minister Lloyd George in his memoirs, “but rather that within its boundaries several free autonomous states should be created on the model of the British Empire.

On 9 January 1918, Lloyd George, speaking in the English Parliament, said that “the task of British policy does not include the destruction of Austria-Hungary. And the Entente powers intended to keep their hand on the pulse of the Austro-Hungarian events and direct them as they saw fit: “The discontent of the nations in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy must be fomented,” said a memorandum of the International Commission of Experts on the Study of the Peace of December 22, 1917, “but at the same time to forestall the far-reaching consequences which are produced by this discontent and may lead to the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy”.

These plans of the Entente were clearly at odds with the aspirations of the Southern Slavs. The Yugoslav Committee immediately after Lloyd George’s statement expressed its disagreement with the British Prime Minister, noting that the English plan contradicted the principles of the Corf Declaration.

Meanwhile, the Austro-Hungarian government was making desperate efforts to get out of the war. It had already been realized in Vienna that, if defeated, events in the country would become unmanageable. Secretly from Germany, Viennese diplomats were engaged in separate negotiations with the Entente. Particular attention was paid to the negotiations in Brest-Litovsk, which began on December 22, 1917. Here, representatives of Germany and Austria-Hungary discussed with representatives of Soviet Russia the terms of peace. Count Otokar Chernin, head of the Austrian delegation to the negotiations, received reminder telegrams from Vienna almost daily: “The fate of the empire depends on the success of the negotiations,” Emperor Karl wrote to Chernin. “The public of the country thinks of nothing else but peace,” telegraphed Austrian Prime Minister Seidler. And when Trotsky, head of the Soviet negotiating delegation, uttered his historic phrase: “No peace, no war, and the army disbanded,” and it became clear that the negotiations had broken down, a general political strike on an unprecedented scale began in Austria-Hungary. The sailors of the Austrian navy revolted. Riots began in the army units, a wave of mass demonstrations and rallies swept across the country. In mid-June a second general strike began. It coincided with another major defeat of the Austrian army on the Italian front, after which the mass demoralization of the army began. Entire units deserted from the front.

In the fall of 1918 the agony began. On September 14-15, Serbian and French forces broke through the Salonika front and launched an offensive in Macedonia. On September 29 Bulgaria capitulated. On October 4, the government of Austria-Hungary sent a note to the Entente powers, in which it proposed to begin peace negotiations. On October 5 began a massive attack by Entente troops on the Italian front.

This was the end of the empire. Virtually the entire territory of the country was already out of Vienna’s control. On October 6, in Zagreb, the National Veche of the Yugoslav Peoples was formed, which included representatives of Croatia, Slovenia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. On October 16, Emperor Charles issued a belated manifesto reorganizing the monarchy, but this act only hastened the collapse of the empire. The People’s Veche began the formation of its own authorities and proclaimed its program, the goal of which was “the unification of all Slovenes, Croats and Serbs into a popular, free and independent state, established on democratic principles.” The unification of the Yugoslav population was to take place “over its entire ethnographic territory, regardless of the regional or state boundaries within which it currently resides.” At the end of October mass uprisings of the Yugoslav units of the Austro-Hungarian army began. And on October 29, the People’s Veche in Zagreb passed resolutions to break with Austria-Hungary, separate all the Yugoslav provinces from it, and establish an independent State of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs.

On November 4, Austria-Hungary capitulated.

Immediately after the declaration of independence, the People’s Veche declared an end to the war with the Entente and demanded that the new state be granted the right to participate in a peace conference. The People’s Council authorized the Yugoslav Committee in London, which had offices in other capitals of the Entente countries, to represent the interests of the new state in the international arena. Inside the country, the formation of local authorities and its own armed forces – the People’s Guard – began. The need for its own army was strongly dictated by the difficult international situation in which the country found itself. Through its territory the masses of demoralized Austro-German troops were retreating from the Salonika front, Serbia and Montenegro, looting and plundering along the way. Gangs of deserters terrorized the population. There were riots in a number of towns. Anarchy threatened to engulf the entire country. With the collapse of Austria-Hungary and the complete disorganization of its state institutions, the Italian army occupied the entire Adriatic coast with the cities of Trieste, Rijeka, Split, Dubrovnik. Under these circumstances, the People’s Veche was forced to summon Entente troops into the country.

The occupation by Italy of the vast coastal zone alarmed France and Serbia. Both countries were not interested in strengthening Italy’s position in the Balkans. Therefore Paris immediately made a vigorous diplomatic demarche against the Italian action, and the Entente military command introduced French and Serbian troops into the territory of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs.

The Serbian government remained on the island of Corfu until November 1, 1918, from where it closely monitored events in the Balkans. On November 1, Serbian troops liberated Belgrade, and on November 13 an armistice was concluded between Serbia and Hungary. Serbian Prime Minister Nikola Pashic, at a meeting of the leaders of the Entente states in Paris, demanded that his country make territorial compensation for the damage caused by the Austro-Hungarian occupation. But there was no question of the annexation to Serbia of all the former Austro-Hungarian territories inhabited by the Yugoslavs.

The leadership of the great powers was calculating the options for action. With the end of the world war the geopolitical situation in Europe had changed considerably. Russia, Germany and Austria-Hungary disappeared as a factor in European politics. The new balance of power gave rise to new contradictions. The strategic importance of the Balkans lay in their proximity to Turkey and the Arab East, from where one could control the entire eastern part of the Mediterranean. But France was now the de facto hegemon in the Balkans. Displeased with this, England and the United States sought to limit French influence. It was with their support that the Italian occupation of the Balkans began. However, having authorized this move, London and Washington soon became concerned that the Italians would grab too much, and that over-strengthening Italy was not in their plans. As a result, British and American troops began to land in the Yugoslav ports seized by the Italians.

The situation urgently demanded a balance of power in the Balkans. The only counterbalance to Italy could have been a large Southern Slavic state in close alliance with the Entente. This would suit everyone except Italy, but it was not at issue in this context. In addition, the new state in the Balkans, according to the Entente, was to be an important element of the “cordon sanitaire” around Russia, struck by the plague of Bolshevism.

Neither the National Council of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, nor the Serbian government objected to unification. But political parties, factions, and movements had different, often diametrically opposed views on the principles of the future state.

Yugoslav social-democratic circles advocated a republican form of government, the equality of all the peoples of Yugoslavia and a federation of democratic republics. The leading Croatian political parties insisted on the autonomy of Croatia in a unified Yugoslav state. Serbian nationalists viewed the creation of a unified Yugoslavia as a legitimate “war prize” for Serbia. The people of Macedonia favored autonomy or full independence for the country. In and around Montenegro there was a fierce struggle between supporters of the country’s independence and supporters of unification with all the Yugoslav peoples. King Nicholas of Montenegro and the royal government in exile had the support of Italy, which expected to maintain an independent Montenegrin kingdom and use it as a springboard to expand its influence in the Balkans.

These plans were actively opposed by France. By that time Paris had managed to completely subdue the Serbian royal court, the Serbian government and generals, and, with the help of military loans, Serbia’s finances. In France’s plans, Serbia was to become the main agent of French influence in the Balkans, uniting all the Yugoslav peoples around itself.

France’s intentions were disapproved of by the United States and England. They would be much more satisfied if there were several weak states in the Balkans which would be easy to keep under control. Therefore, in the Montenegrin question, the U.S. and England supported the supporters of King Nicholas. U.S. President W. Wilson, even in the case of a united Yugoslavia, offered to maintain an autonomous Montenegro under the rule of the Montenegrin royal dynasty. The struggle around the “Montenegrin question” continued until the death of King Nikolaj in 1921. In January 1919, supporters of the Montenegrin king even initiated an armed rebellion, which was suppressed by Serbian troops.

In November 6, 1918 a meeting of the representatives of the Serbian government, the Yugoslav committee and the National council of the state of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs opened in Geneva on the harmonization of positions. After difficult negotiations, it was possible to adopt a declaration on the need to unify the Yugoslav lands into a single state.

On November 24, 1918 the National Council made a decision on the unification of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs with Serbia and Montenegro. On November 26th the decision on joining with Serbia was adopted by the National Assembly of Montenegro. And on December 1, 1918 on behalf of the king, Prince Regent Alexander Karadjordjevic announced the formation of a single state of Yugoslavs – the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. This date is considered the date of creation of Yugoslavia.